"A Woe of Ecstasy":

On the Electronic Editing of Emily Dickinson's Late

Fragments

The Living Archive: A Brief History of Scatters

In 1999, I published the first version of Radical Scatters: An Electronic Archive of Dickinson's Late Fragments and Related Texts with the University of Michigan Press. It was among the first works to be published in the Press's Digital Text Series, and it was one of the very few works in that series to be published online and distributed via a site license, rather than sold in CD-Rom format. At the time, the question of publication platform was a vexed one. While the CD-Rom format would almost certainly have made the archive more immediately visible to the diverse community of Dickinson readers and scholars, the online format offered other, less immediate and certainly less visible, advantages. Most importantly, it offered the possibility of creating a "living" archive—a work that, unlike a CD-Rom (or a standard edition), could grow and change over time. Moreover, the heterogeneous and even fundamentally unstable nature of the archive's contents seemed almost destined for representation in the zero gravity of hyperspace, where forces of unseen connectivity seem to be at work, but where the concept of teleology is largely absent. And so the decision was made. ✝ This decision was influenced both by many people, mostly textual scholars and editors, whose critical farsightedness and experience using in the new medium inspired me to take the risk of publishing an online archive. I remain especially grateful for the counsel of Jerome J. McGann, George Bornstein, Peter Shillingsburg, David Greetham, Speed Hill, Martha Nell Smith, Matthew Kirschenbaum, John Price-Wilkin, Christina Powell, and John Unsworth. Yet as time passed, Radical Scatters seemed to recede into this deep space, receding at last so far as to almost vanish from view entirely. Only a very small band of textual scholars, and a still smaller band of Dickinson scholars, seemed aware of its existence of at all, and there were even moments when I wondered whether my four years of hard work on the fragments had taken place in a dream. Thus one day in 2006, when I received an e.mail from the University of Michigan Press informing me that the Press was no longer able to support its online, site-licensed archives and planned to declare them out-of-print, I imagined that Radical Scatters was soon to fall into a black hole from which there would be no return. ✝ The University of Michigan Press eventually found a way to keep Radical Scatters by having the site licenses distributed by another university press. While I appreciated the Press's efforts to "save" the archive, I was not convinced that the solution was ideal, especially as it did not address my interest in exploring the potential of digital archive for transformation. It's my hope that a digital copy of the first incarnation of Radical Scatters may be preserved in order that scholars may trace the changes from version to version. I inquired after the files—were they safe?—but their status was unclear. And, worst of all, the map of the archive, the "DTD," had seemingly been lost. ✝ The loss of the SGML DTD along with the XSLT files was both inexplicable and serious; it created a great deal of extra work for the staff at the CDRH. I am immensely grateful to Katherine L. Walter, Brian Pytlik Zillig, and Laura Weakly for their willingness to reconstruct the lost data.

Yet what appeared to be the end of the archive was, in fact, only a turning point in its history. By the end of 2007, Radical Scatters moved from the server of University of Michigan Press to its new home at the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities (CDRH) at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. This move is a salutary one for several reasons. In addition to preserving archive's contents, the move to the CDRH allowed me the opportunity to update the archive by adding several additional fragments that have come to my attention since 1999, making minor corrections to the e.text transcriptions of Dickinson's manuscripts, and converting the archive's SGML files to XML files. The move has still larger implications. Although the policies of the Harvard University Press continue to prohibit free access to Radical Scatters, the archive will be available by subscription to individuals as well as institutions—archives, colleges and universities, etc. ✝ The transfer will take place in this summer (2007) and, hopefully, be completed by late fall of 2007. The subscription prices for individuals and institutions have not yet been determined, but further information should be available soon. Scholars seeking rights to reproduce primary materials from the archive must continue to apply to the manuscript holders (Amherst College, the Houghton Library, etc.) and to the Harvard University Press. Those seeking permission to reproduce diplomatic or e.text transcriptions from Radical Scatters would apply directly to the directors of the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Moreover, while at the University of Michigan the archive was a beautifully mounted but also solitary and isolated site, at the CDRH Radical Scatters will be linked to other nineteenth-century sites, including The Dickinson Electronic Archives and The Walt Whitman Archive, through a connection with NINES, the Networked Infrastructure for 19th-Century Electronic Scholarship. The use of Collex, "a collections and exhibits tool for the remixable web," will enable deep searching of Radical Scatters, as well as make possible the aggregation, collection, annotation, and sharing of related online scholarship. ✝ 5 The quoted passage is composed by the editors of the NINES site (http://www.nines.org/collex). I am currently working with Katherine L. Walter, Co-director of the CDRH, to prepare a formal application for adding Radical Scatters to NINES.

The essay that follows, begun years ago and reconceived in light of the transfer of Radical Scatters from Michigan to Nebraska–Lincoln, marks two moments in my thinking about Dickinson's fragments and about the archive itself: it records my thoughts of the mid-1990s, the time of my initial encounter with the fragments, when I was primarily concerned with the problems of representing these texts as fully and accurately as possible; and it reports my reflections, almost a decade later, on the limits of encoding the fragments and on the ways in which they continue to escape the analytic operations we apply to them. This is, of course, no reason to stop talking. It is, on the contrary, an invitation for continued conversation about the editing and interpretation of all of Dickinson's writings.

To the Lyric's Many Ends: The Fragment in Literary Scolarship

Literary scholarship concerns itself with works as finished products, as texts that lack nothing and in which nothing is superfluous. . ..That is why the fragment, which does not fulfill the presuppositions of wholeness, is not a popular object for literary scholarship and perhaps not even a possible one. The fragment cannot be controlled. Thus the encounter with literary scholarship with the fragment creates a contradictory situation. Either the discourse about the fragment must deny it as what it is and falsely make it into a whole, or it must itself be put into question in its claim to master the text. . ..The fragment can only be approached by a discourse with no claim to power. —Hans-Jost Frey

Once again, I come to you from the region of Emily Dickinson's late work, the writings of the 1870s and 1880s, and, more specifically, from the remote precinct of her fragments. Like the limit texts of other writers—Kafka's Conversation Slips, Pascal's Pensées, and Wittgenstein's Remarks on Colour come to mind—Dickinson's fragments are essentially private writings, belonging more clearly to the space of creation than communication. ✝ For an interesting discussion of these two "spaces," see Louis Hay, "History or Genesis?" Yale French Studies 89 (1996): 191–207. Never prepared for publication, perhaps never even meant to be read by anyone other than the scriptor herself, they are not so much "works" as symptoms of the processes of composition, data—aleatory, contingent—of the work of writing. Nothing is less likely than that the fragments discovered among Dickinson's papers after her death constitute a unified collection of texts. On the contrary, the connections among them are at most transient. If, at times, it seems that one or two or even several act as "strange attractors," drawing near to one another, forming a small constellation, at other times each appears as a separate, antinomic text, remote from the others, unassimilated and unassimilatable to a larger, totalizing figure. At last, it is as if the uncertainty of the fragments' provenance commits them to an equally uncertain future. Freed from the forty bound fascicles, those accumulated libraries of Dickinson's poetic production, they fly outside the codex book to the lyric's many ends.

From Closure to Contingency: Editing Dickinson's Bibliographic Fugitives, 1950–present

When I first began to think about editing Dickinson's late fragments, many questions swirled in the air without ever settling. They had last been edited in the 1950s by Thomas H. Johnson, when he printed some of them in footnotes in the Poems and others, seemingly as an afterthought, in the Appendices of the Letters. In both cases, the fragments, either subordinated to more finished texts (as in the footnotes) or stripped of their original material contexts (as in the Appendices), disappeared from view almost in the very moment they had first appeared in print. In retrospect, it could not have been otherwise: the apparent failure of Johnson's imagination vis à vis Dickinson's fragments was historical, not personal: the prevailing emphasis on "final authorial intention" in the editorial ideology of the 1950s—one way of mastering the text—blinded editors and readers alike to the potential significance of these fugitives. Furthermore, though this case has yet to be made in any rigorous way, it is possible, even probable, that the editorial ideology of the 1950s developed in direct relation to the cultural trends in the United States toward containment and isolationism. The "Cold War" attention to national borders may thus be reflected in a similar attention to textual borders—a need to define and contain texts—and, ultimately, to privilege the finished text over the turmoil of compositional process. In such a milieu, the fragments could only be seen as "superfluous," an embarrassing excess. Thus while they were composed in the last decades of the nineteenth century and initially printed in the middle of the twentieth, it may be argued that Dickinson's fragments could not become fully visible until the beginning of the twenty-first century when, in the transit from modernity to postmodernity, claims for the work's stability were replaced by the acknowledgement of its essential contingency. ✝ For a fine introduction to this shift in textual scholarship, see, for example, Palimpsest: Editorial Theory in the Humanities. Eds. George Bornstein and Ralph G. Williams. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1993.

The postmodern redefinition of textuality, like the modern one preceding it, did not arise sui generisly. The sudden swerving into focus of the work's contingency may only have occurred alongside our larger awareness of narratives of cultural and political diaspora. Indeed, as Homi Bhabha notes so eloquently in Location and Culture, it is our age more than any other before it that recognizes that the epistemological limits of our cultural master narratives "are also the enunciative boundaries of a range of other dissonant, even dissident histories and voices" (936). Homelessness is our inheritance and our condition. A poetics of exile, of the margin, is our rejoinder.

Not surprisingly, in this new demography, the conventional modes of communication—cultural, textual—also underwent powerful changes. Under the postmodern sky, the horizon of the codex edition suddenly appeared too low, too dark, or perhaps only too near in comparison with that of the electronic medium. In the latter was the promise, still barely fulfilled, that even the most problematic primary materials might circulate in the freer, if more rarefied air of hyperspace, open to all eyes. ✝ Of course, pace Sven Birkerts, the codex edition has not vanished—and will not, at least in the foreseeable future. Indeed, the interplay of codex and digital editions, far from producing the "morbid symptoms" Birkerts sees everywhere, has revivified textual studies, and especially manuscript studies, in exciting ways. Moreover, and for less clearly understood reasons, the flowering of the electronic medium, and, especially, of the digital archive, signifies the very deep desire of our time for speed, transience, openness, and, ultimately, for distance. This medium, more than any other, seems to reflect and produce the very contingency and even homelessness we accede to.

My work in Radical Scatters: An Electronic Archive of Dickinson's Late Fragments and Related Texts is at once an attempt to effect a richer revealing of these bibliographical escapes in their own time and a case study of a late moment in the history of their representation. Indeed, without the convergence of the very specific conditions noted above, as well as many others that remain unnoted and even unknown at the present time, it is unlikely that Radical Scatters would ever have been conceived, let alone come into being, and I remain convinced that its primary value—if it has one at all—is as a witness to the constant, if not always conscious, collaborations between scholarship, history, culture, and technology. It is possible, moreover, that in the process of working on the fragments, others will find that they reveal a secret affinity between Dickinson's late thinking and our own thinking at the end of a century.

Unforeseen and Anomalous Orders: Core Texts and Document Constellations

The core of Radical Scatters consists of eighty-two documents carrying over one hundred fragmentary texts composed by Dickinson in the final decades of her life. ✝ The precise number of texts, as opposed to documents, is withheld, since that number is based on the interpretation of textual boundaries and is thus subject to change. In addition to the core texts, the archive's primary materials include fifty-three poems, letters, and other writings by Dickinson with direct links to the fragments. While the manuscripts of the fragments are housed at the Amherst College Library, the manuscripts of the related texts are divided among seven libraries—Amherst College Library (29), Houghton Library (12), Boston Public Library (6), New York Public Library (1), Yale University Library (1), Princeton University Library (1), The Rosenbach Museum and Library (1), the Jones Library, Inc. (1)—and one private collection (Oresman, 1).

The criteria for inclusion used in this version of Radical Scatters are as follows: all of the fragments featured as "core" texts have been assigned composition dates of 1870 or after; all of the core fragments are materially discrete; and all of the core fragments are inherently autonomous, whether or not they also appear as traces in other texts. ✝ Excluded from this version of Radical Scatters are fair- and rough-copy message drafts to identified and unidentified recipients unless the message draft also exists as an independent fragment or has been deliberately excerpted—usually cut out—of a longer message and preserved among Dickinson's papers; brief but apparently complete poems and poem draft; extra-literary texts such as recipes and addresses; quotations and passages copied or paraphrased from other writers' works; and textual remains preserved apparently only accidentally because Dickinson used the same writing surface to compose other texts. A file of control texts containing facsimiles of documents and texts drawn from Dickinson's late writings but not included among Radical Scatters' core documents is included in the archive to help clarify the criteria used to determine whether a given text belongs in the present configuration of late writings and, conversely, to foreground the difficulty of definitively demarcating the boundaries between Dickinson's late fragments and the other bibliographically ambiguous texts found among her papers/of the same years. Of the approximately one hundred extant fragments I took as my point of departure, almost half descend to us as independent passages, as brief texts that either have no direct links to other poems or letters in Dickinson's oeuvre or whose links to these texts is now irretrievable. Like Emerson's souls, neither touching nor mingling, never composing a set, these positionless fragments depict the beauties of transition and isolation at once. Belonging to a chronology of the instant, vulnerability is the mark of their existence: they belong, if at all, to a discontinuous series, or to a "book from which each page could be taken out" (Cixous 105).

The remaining fragments are "trace fragments," or fragments—sometimes avant-textes, sometimes inter-texts, sometimes post-texts—associated with a larger constellation of poems, letters, or drafts among Dickinson's papers. Again and again, as if poems, letters, and fragments communicated telepathically, a line or phrase from a fragment re-appears, often altered, in the body of a poem, a message, or even another fragment. Yet the painstaking effort to identify all such trace fragments and link them with the texts in which they appear fails to effect any lasting closure: neither residents nor aliens, neither lost nor found, these trace fragments are caught between their attraction to specific, bounded texts and their resistance to incorporation. Instead, they require that we attend to the mystery of the encounters between fragments, poems, and letters, listening especially to the ways in which, like leitmotifs, the fragments both influence the modalities of the compositions in which they momentarily take asylum and carry those leitmotifs beyond the finished compositions into another space and time. ✝ This brief reading of autonomous and trace fragments was first offered in my essay, "'Most Arrows': Autonomy and Intertextuality in Dickinson's Late Fragments," TEXT 10 (1997): 41–72.

The inclusion of fragments belonging to a constellation of texts—i.e., trial beginnings, re-workings or repairs of textual situations, etc. of a given poem or letter—is especially vexed. In instances where there are several possible "fragments" in a given constellation, I have in general selected the briefest and most difficult to classify text as the "core" document, while also attempting to specify its relationships to other associated texts. Thus although it has been my intention to include all of the late fragments possessing aesthetic or formal integrity, the term "fragment" is itself a problematic one, and the list of contents must be understood as provisional rather than definitive. The fragments in Radical Scatters offer only an entry point into the mass of late, unbound, extra-territorial writings in Dickinson's oeuvre. In the future, some of the documents included in the present archive will fall outside of it, while others, not yet identified as fragments, will enter it, producing not new "collections" but, rather, unforeseen and anomalous orders. ✝ The following documents, for instance, identified in R. W. Franklin's The Poems of Emily Dickinson (1998), might be included in a new incarnation of archive: A 135 / 136; A 173; A 210a; A 266 / 267; and A 429. For further information on these texts, see P 1304 (A); P 1364 (A); P 1382; P 1384 (B); P 1296 (A); and P 1520 (A) in The Poems of Emily Dickinson. Variorum edition. 3 vols. Edited by R. W. Franklin. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap P of Harvard UP, 1998.

Crossing the Line: From Edition to Critical Inquiry

In undertaking a new representation of these texts first in the 1990s and now, almost exactly a decade later, I have been aware of my very different, sometimes opposing relations in regard to them. On the one hand, I have tried to restore as far as possible their material integrity and to give readers unmediated (or, rather, less mediated) access to Dickinson's manuscripts as she left them. In so doing, Radical Scatters encourages new investigations into both the dynamics of Dickinson's compositional process and the play of autonomy and intertextuality in her late work. On the other hand, I have continually crossed the line of the scrupulous archivist and the strictly documentary editor by initiating the interpretive process from inside Radical Scatters. To put this another way, I have not been content simply to lay the ground work from which investigations into the significance of the fragments may begin, but I have actively begun the investigation. In this sense, I am less "pure" archivist or editor than critic and translator. And in this sense, Radical Scatters, too, despite its title, is not so much an archive—or, as others have classified it, an edition—as it is an experiment in reading Dickinson by editing her and a case-study in editing Dickinson by reading her. It may be best understood as a first attempt to develop a new paradigm for representing Dickinson's most bibliographically problematic texts and thus as a testing ground for theories of representation that may, at a later time, be applied to the digital representation of her complete writings. ✝ 13 The structural principles underlying the organization of the archive's files and the representation of the documents contained within it may not be applicable, without serious modification, to an electronic archive of Dickinson's bound poems or, for different reasons, to an archive of her correspondences. Yet editing and encoding Dickinson's late fragments will help to identify problematic issues in the editing and encoding of all of her writings and to indicate the degree of standardization still required to create a hypermedia archive of Dickinson's complete writings. Thus while there is as of yet no formal association/link between Radical Scatters and the Dickinson Electronic Archives, they remain in productive dialogue with one another. Radical Scatters' move from the University of Michigan to the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, will facilitate this dialogue: for while at Michigan, Radical Scatters existed as a discrete and isolated site, at Nebraska–Lincoln, and through linkage to NINES, it will be in communication with the DEA and various other 19th-century archives.

To note this is to admit at once that Radical Scatters has none of the grandeur of the vast digital archives—e.g., The Blake Archive, The Rossetti Archive, The Whitman Archive, The Dickinson Electronic Archives ✝ In her recent essay, "The Human Touch: Software of the Highest Order" (Textual Cultures 2:1 [Spring 2007]: 1–15), Martha Nell Smith has noted several important ways in which the Dickinson Electronic Archives itself departs from the centrifugal organization typical of digital archives. Her use of "digital samplers" and the "Virtual Lightbox," especially, make visible the interpretive consequences of textual scholarship., and so many others currently being prepared all over the globe. Nor does it have the authority associated with "definitive" or variorum editions of Dickinson's writings, most notably Ralph W. Franklin's The Poems of Emily Dickinson. Its value lies instead in its devotion of maximal energy to minimal contents and in its counter-inductive organization. Most importantly, unlike both large-scale digital projects and variorum editions, which tend to begin by presenting "major" works, then add "minor works" over the course of their development, Radical Scatters proceeds by foregrounding "minor" works in order to see how they might illuminate the "major" works contained both inside and outside the fascicles. Indeed, as scholars in diverse fields of inquiry have recognized, limit-works seem capable of illuminating with particular clarity the principles at the core of an artist's production. In Dickinson's case, the fragments, the limit texts, are the latest and furthest affirmation of a centrifugal impulse, a gravitation away from the center, that is expressed at every level and at every phase of her work, and is revealed in the starkest possible manner in the leading formal problem of Dickinson's work: the problem of variant readings. ✝ On the importance of late work, see, for example, Theodor W. Adorno, "Late Style in Beethoven," in Essays on Music, ed. Richard Leppert, with new translations by Susan H. Gillespie (Berkeley: U of California P, 2002), and Edward W. Said, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York: Pantheon, 2006).

As a close reading of the fragments shows us, the contest played out in the poems of the 1860s between a word (or phrase) and its variant(s) is never resolved. Rather, in the 1870s and 1880s, Dickinson carries the tendency in her work toward difference and différance to its furthest ends, at last abandoning the idea of the "work"—"poem," "fascicle," "oeuvre"—in order to engage a poetics of writing; in so doing, she sets in motion a new kind of work, a work without beginning or ending, a work in throes. And thus to recall Bhabha again, the "dissonant and dissident histories" of the fragments attest to the need for an approach to Dickinson's work that aims not toward the poems'—or writing's—final resettlement, as in an archive or a variorum, but toward their—its—restoration to a world of contingencies.

The insights the extra-territorial texts at the margins of Dickinson's oeuvre offer us, their laying bare in beautiful and often shocking ways the unhomeliness of [her] poetry's condition—as well, of course, as our own—cannot fail to have important implications for Dickinson scholarship in general. The powerful feminist readings of the late seventies and the eighties, which revealed a complex image of Dickinson, are deepened and affirmed by the poet who appears in the fragments, as are the more recent and very compelling queer readings of Dickinson. The incisive analyses of Dickinson's work alongside the work of her culture that arose in the late eighties and revealed one source of her fractured writing in the fractures of the Civil War and the crisis of faith that attended it, are likewise complemented by this Dickinson speaking-writing in extremis. The seminal readings of Dickinson's language—her broken grammar and syntax, her and strange use of the sonic qualities of language—are evident in her late manuscripts, whose visual qualities underscore, even double, her verbal experimentations. And finally, textual scholarship itself is impacted by the revelations of the fragments. As I have argued elsewhere, the focus on the fragments—the endpoint of Dickinson's poetic production—suggests that the fascicles are not the culmination of Dickinson's poetic production but a "middle passage" in her poetics of radical inquiry. ✝ See, for example, my essays "'Most Arrows': Autonomy and Intertextuality in Dickinson's Late Fragments." Text 10 (1997): 41–72, and "The Flights of A 821: Dearchivizing the Proceedings of a Birdsong," in Voice, Text, Hypertext: Emerging Practices in Textual Studies, eds. Raimonda Modiano, Leroy F. Searle, and Peter Shillingsburg (Seattle: U of Washington P, 2004): 298–329. Moreover, the extrageneric status of the fragments—as well as the existence of fragments in both prose and verse—suggests the need to reimagine the boundaries between "poems," "letters," "drafts," and "fragments."

In Radical Scatters, the influence of feminist, new historicist, deconstructionist, postcolonial, and queer approaches to the text are registered in varying degrees in the conceptual structure of the work as well as in the local transcriptional and encoding practices. Likewise, the collision and collusion of textual scholarship and critical theory in the 1990s, along with the publication of landmark works in the field—e.g. The Manuscript Books, edited by Ralph Franklin, and the early trailblazing responses to these editions by Susan Howe, Martha Nell Smith, and Sharon Cameron—exerted a profound influence on the direction of Radical Scatters. Though the focus of the work offered by Franklin, Howe, Cameron, and Smith—generally the fascicle poems or the letters—was different from my own, their concern with the materiality of the text resonated with my interest in the late manuscripts. ✝ See, especially, Susan Howe's "These Flames and Generosities of the Heart: Dickinson and the Illogic of Sumptuary Values," first published in Sulfur 28 (Spring 1991): 134-161, and later reprinted in The Birth-Mark: unsettling the wilderness in American literary history (Middletown: U of Wesleyan P, 1993); Martha Nell Smith's Rowing in Eden: Rereading Emily Dickinson (Austin: U of Texas P, 1992); and Sharon Cameron's Choosing Not Choosing: Dickinson's Fascicles (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992). Finally, the many examples of digital archives—though I would depart from them in significant ways—were ever before me, challenging me to ask new questions of the fragments and to conceive of new ways of representing them outside the confines of the codex edition.

Transcription as Translation

Work on Radical Scatters proceeded in two stages: first, the transcription of the documents; and second, the imagination of a schema for organizing the archive's contents that would enable their analysis without disabling their autonomy or effecting their closure. ✝ The first incarnation of Radical Scatters is in large part the result of my creative collaboration with Christina Powell and John Price-Wilkin, both then senior staff members at the Collaboratory at the University of Michigan; likewise, the second (present) embodiment of Radical Scatters was the result of an on-going collaboration with Katherine L Walter (Co-director, CDRH), Brian L. Pytlik Zillig (Digital Initiatives Librarian, CDRH), Zacharia A. Bajaber (Digital Resources Designer, CDRH), and the staff of the CDRH at the University of Nebraska—Lincoln. Following Peter Robinson's seminal work on the transcription of primary textual sources for the computer, I approached the act of transcribing the fragments "not as an act of substitution, but as a series of acts of translation from one semiotic system . . . to another" (7). Like all acts of translation, these acts of transcription are "fundamentally incomplete and fundamentally interpretive" (Robinson 7). In Radical Scatters facsimiles, diplomatic transcriptions, and xml-encoded e.texts attempt to record and represent as many of the characteristics and dynamics of the original manuscripts as possible. Each, moreover, interprets the manuscripts from a different perspective: diplomatic transcriptions foreground the spatial dynamics of Dickinson's writings; e.text transcriptions foreground the temporal dimensions of her writing; and facsimiles impart to these "flat" interpretations of the manuscript a kind of virtual depth. While the goal of the diplomatic and e.text transcriptions is the production of a legible text, the facsimiles emphasize the essential otherness—what Edward Bullough called the "psychical distance"—of the manuscripts as well as our estrangement from the original scene of their composition.

Facsimiles: Enigma

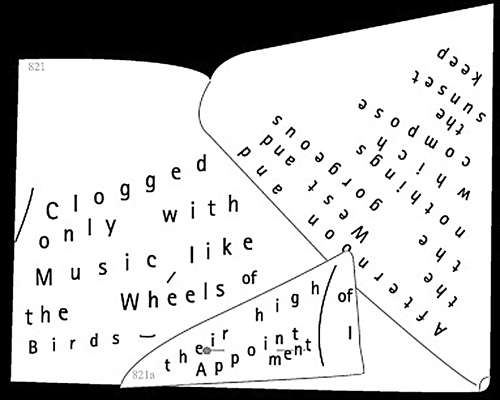

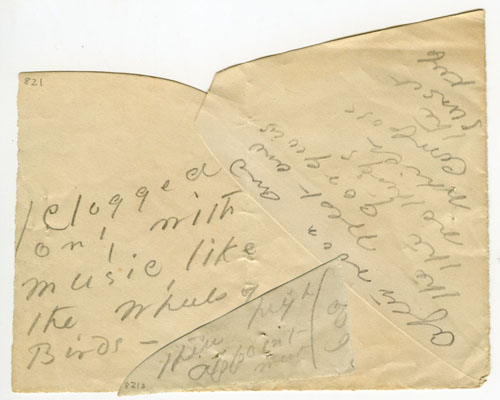

Focus 1: Facsimile, A 821, A 821a. Last decade. A rough copy pencil fragment on two scraps of an envelope held together with a straight pin. A 821 measures approximately 102 x 107 mm.; A 821a measures approximately 31 x 64 mm. There are ten pinholes on A 821 and four on A 821a.

The manuscript is the text's "other scene," the record, only partly discursive, of a vision that cannot ever be completely decoded or encoded. Its refusal to disclose itself fully and at once reminds us of the perpetual need for a method (and a theory) of translation attentive to the dialectics of access and otherness, darkness and divination, writing and seeing. On the surfaces of Dickinson's manuscripts the turbulence of the mind expresses itself in a series of legible signs and illegible marks—in letters, dashes, pointings, strike-outs, pen tests, blurs, blank spaces. Some of the signs, especially the alphabetic symbols, we believe we know how to decipher and interpret; others, such as the angled dashes and flying quotation marks, we recognize as expressive, but interpret awkwardly; still others, not signs, even, but subsemiotic marks made accidentally by the author, time, or the elements, we cannot interpret, though we sense intuitively that they, too, are part of the manuscript's environment and contribute in some way to its signification.

In order to produce high-quality images of Dickinson's manuscripts, the documents were first photographed using Kodak 64T color film with tungsten lighting, then converted to digitized images, and finally sized and color-corrected in such a way as to make Dickinson's handwriting clearly visible, but without distorting the appearance of the image. ✝ Whenever possible facsimiles of the manuscripts of the fragments and related texts have been included in the archive. In six instances the manuscript of a fragment or related text has been destroyed or lost; in cases where an early transcript has been preserved, I have included an e.text rendering of the transcript in place of the manuscript; in cases where such transcripts do not exist, I have included an e.text rendering of the most authoritative printed source of the text. The Houghton Library, which houses twelve manuscripts with links to core fragments in this archive, and the Princeton University Library, which houses one manuscript with a link to a core fragment in this archive, do not permit the publication of images of Dickinson's manuscripts on the World Wide Web. For the present, viewers must rely on the diplomatic transcriptions and bibliographical descriptions of these documents provided. Thus while the facsimiles are necessarily "surrogates" for the original manuscripts, they nonetheless reveal the contours as well as many physical features—edges, folds, creases, watermarks and embosses, damage—of the original manuscripts as well as changes in writing instrument, gradations in the colors of inks and the thicknesses of leads, evidence of overwriting, scraping out, and erasure. ✝ "Surrogate" is the term Martha Nell Smith uses (see "The Human Touch: Software of the Highest Order" [Textual Cultures 2:1 (Spring 2007): 1–15], to distinguish between facsimiles and original manuscripts, and to make clear that the facsimile is never a perfect substitute for the original.

The facsimiles are the most luminous witnesses of Dickinson's original manuscripts; the sensitive calibration of technology's instruments reveals as no print translation can the "layerings and fragile immediacies" (Howe 19) of the handwritten artifacts abandoned by Dickinson more than a century ago. Paradoxically, the expectations of Parousia are not—and never can be—fulfilled: at the same moment that the facsimile illuminates the document it also confirms the radical absence of the "original" not only from the electronic archive but also from the library collection that claims to house it but which instead contains another artifact, the original altered by the imprint of history and the "stigmata of past experience" (Foucault 83).

"Faraway, upclose!" as Wim Wenders said—or: "Upclose, faraway!" ✝ This quote is the English title, translated from the German, of Wim Wenders's film In Weiter Ferne, so nah! (1993).

Diplomatic Transcripts: Scrawl

Focus 2: A 821, A 821a diplomatic transcript.

In "All Writing Is Drawing: The Spatial Development of the Manuscript" Serge Tisseron remarks: "The current technological evolution is drawing noticeably closer to the conditions presiding over the manual creation of a manuscript. . . . Whereas the earliest typewriter technology estranged the user from the process of marking, the current developments tend toward a reconciliation with it" (30). Radical Scatters uses print technology in combination with MacroMedia Freehand and Adobe Photoshop to accommodate various aspects of Dickinson's scribal practice, and thus effect a partial escape from print, from the logic of identity and fixity.

The method of transcription used here developed in response to the particular demands of Dickinson's scriptural styles and interstitial page design. ✝ I was fortunate, while teaching at Georgia State University, to have the aid of Patrick W. Bryant, then a Ph.D. candidate in American literature and an early advocate for humanities computing, as my graduate assistant. His help in preparing the diplomatic transcriptions was crucial to the project as a whole. The "we" in this section of the essay refers to Patrick Bryant and me. We began by calling a facsimile of the manuscript to be transcribed to the screen and tracing its contours, seams, and instresses to create a frame and body for the text. Next, we typed directly over the facsimile, reporting as precisely as possible the orthography, punctuation, line breaks, and spaces between letters and words. Though only three fonts were used to distinguish among three constantly recurring scriptural styles (rough-copy; intermediate-copy; fair-copy hand), font sizes were varied according to the size of the handwriting on the individual documents. The often dramatic magnification of letter forms characteristic of the fair-copy texts and the cramped hand of the rough-copy texts are thus partially represented in the diplomatic transcripts. The difficulty, at times impossibility, of distinguishing upper- and lowercase letters served as a constant reminder that even the transcription of isolated characters is fundamentally interpretive. Here, however, only Dickinson's "t" / "T"s were singled out for special treatment: in those instances where the crossbar appears to function as both part of the character and as a dash and/or underlining, the "t" / "T" has usually been traced from the character on the facsimile. A strong case might well be made for treating Dickinson's "S"s, "O"s, and "U"s in the same manner. Indeed, even Franklin's conservative transcriptions in the variorum acknowledge the expressive quality of her letter forms by representing some of her "U"s as "O"s, as, for example, in his transcription of "Four Trees — opon [emphasis added] a solitary Acre —" (P 778). Here, the ambiguity of the letter form—it is neither a perfectly closed "o" nor a fully open "u"—encourages Franklin to make an editorial decision based, perhaps, on a larger interpretation of the poem. The change from "upon," as the word appears in all earlier transcriptions, including Thomas H. Johnson's, to "opon" in the new variorum, effects a subtle but important tonal change. The visual and aural closeness of "opon" to "open" reflects the direction of the poem—and the world it witnesses—toward an unknown (open) end: "What Deed is Their's / Unto the General Nature / What Plan / They severally — retard — or / further / Unknown" (MB II 904).

While we have compromised considerably in the representation of Dickinson's alphabetic characters, we have been less compromising in the representation of her punctuation. Since Dickinson's angled dashes, flying quotation marks, and other pointings are almost always open to interpretation—the distinction, for example, between dashes and periods appearing at the end of a line, is often ambiguous—punctuation marks have been traced directly from the facsimiles. Similarly, strike-outs, underlinings, horizontal and vertical boundary lines, and other kinds of graphic "noise" have been copied from the facsimiles. Finally, in addition to recording marks made on the manuscripts by Dickinson, the diplomatic transcripts offer limited graphic equivalents of joining marks—e.g., the seams of an envelope, the straight pins used to hold texts together—when those joins seem to correspond with significant textual boundaries. Marks made on the manuscripts by copyists, editors, cataloguers, and others appear when still discernible in a grey italic font and in shadow; the attribution and meaning of these marks, when known, is discussed in the commentary accompanying each document.

When a diplomatic transcription is complete, it covers the image of the manuscript, concealing and even appearing to master it. Only, however, for an instant. For at the precise moment when the facsimile is obscured by the transcript, a kind of "kinetic occlusion" occurs: the transcript is "lifted off" and placed behind the facsimile, effecting a sudden restoration of the visible over the legible. While the reader may access the transcript at any time by opening a "floating window" (and creating, if desired, an en face edition), it always returns to its place as an uncanny revenant, a ghost text behind the facsimile. ✝ J. J. Gibson, The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems (Boston: 1966), 203.

Focus 3: A 821, A 821a, "kinetic occlusion."

Electronic Transcripts: Interpretation

Focus 4: A 821, A 821a, xml encoded etext transcription.

Finally, the e.texts, each of which is organized as a structured set of XML-marked descriptions, translate significant information displayed graphically by the facsimiles and diplomatic transcriptions (i.e., salient features of the manuscript's physical appearance and the text's content) into a system designed for search and analysis by computer applications and offer a temporal view of Dickinson's compositional process—that is, they "put time back into the manuscripts" by marking the order in which a series of lines, as well as all authorial interventions including deletions, additions, substitutions, etc., occur (Vanhoutte). ✝ Edward Vanhoutte, "Electronic Textual Editing: Prose Fiction and Modern Manuscripts: Limitations and Possibilities of Text-Encoding for Electronic Editions." Text Encoding Initiative Consortium. http://www.tei-c.org/Activities/ETE/Preview/vanhoutte.xml. 7/2/2007. Thus while the presence, and indeed authority, of the facsimiles in Radical Scatters seems to point backward to the Greg-Bowers notion of copytext, the e.texts are most strongly marked by the influence of European genetic editorial methods, and by the (perhaps impossible) desire to register the progress of the hand/mind across the page as well as the movement of fragments across time zones into poems, letters, and other writings. ✝ For further explanations of the Greg-Bowers theory of copy-text, see W. W. Greg's "The Rationale of Copy-Text," Studies in Bibliography 3 (1950–1951): 19–36; see also Fredson Bowers's "Greg's 'Rationale of Copy-Text' Revisited," Studies in Bibliography 31 (1970): 90–161 and Jerome J. McGann's A Critique of Modern Textual Criticism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983. For a valuable sourcebook on genetic criticism, see Genetic Criticism: Texts and Avant-textes. Eds. Jed Deppman, Daniel Ferrer, and Michael Groden. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2004. Like the diplomatic transcriptions, the e.text transcriptions remain essentially invisible until accessed by the reader.

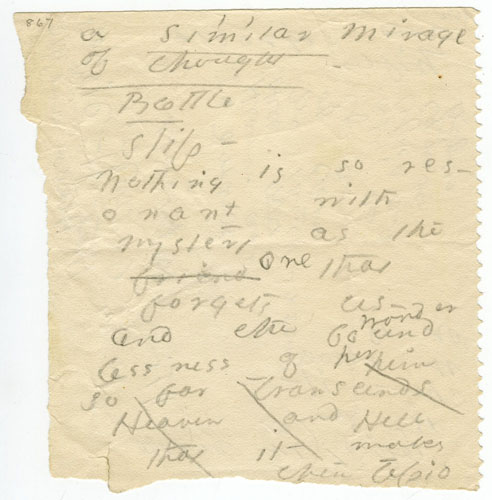

To encode is to discover the far reaches of one's own tyrannizing desire for classification, and Radical Scatters might be understood on some level as a diary of this desire as it gripped me in the nearly two years I spent tagging these one hundred or so documents. From the manuscript body, here understood as the primary level from which all investigations, textual or critical, commence, followed the identification and demarcation of the many texts nesting within that structure, and, finally, the marking of smaller divisions within discrete texts, including passages, stanzas, lines of verse and prose, phrases, isolated words, variants, and traces. ✝ The decision to transcribe all of the texts on a given document runs counter, as I've already noted, to the conventional editorial treatment of Dickinson's late fragments. In Thomas H. Johnson's Letters (1958), for example, the various text fragments inscribed across a single manuscript are often rearranged under editorially determined categories (i.e., "Aphorisms," "To Unidentified Recipients") and printed alphabetically by first line within those categories. They appear in a numbered sequence that no longer reflects their relationship to one another. By respecting the material integrity of the physical document, I hope to encourage speculation about the relationship between the message and the medium in Dickinson's work. The potential of xml to mark as many divisions within a text and relations between and among texts as are visible to the encoder is both the dream that powers the editorial enterprise and the nightmare that threatens to make its realization impossible. For not only is there no end to encoding the text, but at every level of encoding comes uncertainty. In Dickinson's late writings, for example, the division of a series of lines inscribed across a single document into discrete texts is frequently a matter of vexed interpretation, and the assumption that it is possible to mark definitively the line where one text-fragment ends and another begins constantly called into question. Take, for example, the case of A 867:

Focus 5: A 867, facsimile. Last decade. Fragments (in pencil) composed on a torn sheet of wrapping paper marked HENRY ADAMS PHARMACIST and now measuring approximately 110 x 116 mm.

In this case, the relationship of the opening lines—"A similar mirage / of thought -" and "Bottle, Slip"—to each other and to the lines that follows are unclear; all a responsible transcription can do is to mark the uncertain textual borders of the fragments: "<lines> a similar mirage / of thought - <horizontal line> / <isolated words and/or phrases> Bot tle / Slip - / <a867.txt.2; fragment, extrageneric; pencil; ROUGH> <lines> Nothing is so res- / onant with / mystery as the / friend one that / forgets us - / and the bound wonder / lessness of him her / so far transcends / Heaven and Hell / that it makes / them tepid / <reverse (A 867a)> / and / ignoble / trifles <orient: paper rotated one-quarter turn left> so dwarfs / Heaven and / Hell that / we think - recall / of them / if at / all as / tepid and / ignoble / trifles <orient: paper rotated one-quarter turn right> or if / we recall / them it / is as / tepid, / (or / we recall / <orient: paper rotated one-quarter turn right> / It's intricacy is / so boundless / that it dispels / Heaven and Hell" (A 867).

Moreover, while the analysis of Dickinson's late manuscripts brings to light a considerable number of texts, the assignation of text types is often problematic not least of all because so many of the fragments are too brief to be classified definitively as "prose" or "verse," while so many others continually shift between genres (see, for example, A 821). The assumption frequently made by textual editors that types can be determined retrospectively—a fragment incorporated into a poem is a "verse fragment," while a fragment incorporated into a letter is a "prose fragment"—also proves untenable, first because it fails to account for the essential autonomy of the fragment and its resistance to classification, and second because it fails to recognize that the author's intentions toward a fragment may be multiple. ✝ A preliminary list of text types includes the following: fragment (extrageneric); message-fragment; poem; poem (trial beginning); poem-letter; letter, letter-poem; letter (with embedded poem[s]); letter (with enclosed poem[s]); letter (with embedded and enclosed poem[s]); address; practice signatures; pen tests; recipe; ephemera. This list must be treated strictly as a "working list," not a definitive one. In the cases of the poems and letters associated with the fragments, text-types are easier to determine, but divisions within the texts remain problematic. In verse texts, the line has generally been understood as the base structural unit. Yet Dickinson's commitment to metrical experimentation-particularly her breaking out of traditional meters, often leads to considerable uncertainty about what constitutes a line of verse. The frequent non-correspondence in her poems, moreover, between metrical and physical line breaks, further complicates matters. Rather than dividing verse texts into verse lines, I have used the stanza as the basic structural unit. In prose texts, the paragraph is generally recognized as the base structural unit. Yet once again, this proves problematic in Dickinson's case. In the first place, she did not use paragraphs in a conventional way: in her rough copy prose texts there is rarely any clear division of sentences (or lines) into paragraphs; in her fair copy prose texts there is often evidence of division, but the divisions are not always clear both because she did not usually indent the opening line of a paragraph and also because while she often marked shifts of thought/subject by leaving several blank spaces at the end of a line, many shifts remain unmarked because they coincide with the far edge of the page. Second, Dickinson's idiosyncratic punctuation, especially her dashes, often makes it difficult to determine where a given sentence ends. Rather than dividing prose texts into sentences and paragraphs, then, I have chosen in Radical Scatters to divide them into "passages," an inclusive term designating phrases, sentences, and paragraphs.

Similarly, while the syntax of the electronic transcriptions reflects, wherever discernible, the sequence in which a series of words, lines, and marks were inscribed on paper, the wanderings, deletions, and resumptions of writing are not always so easily followed. While at times a very clear record of the successive moments of composition—the hand in the present tense of writing—emerges, at other times no clear record of the trials of writing can be traced, and the representation of temporal dynamics involves an act of speculative reconstruction. Dickinson's introduction of revisions and variants at different moments of the compositional process complicates the representation of temporal dynamics. For example, while it seems logical to imagine that Dickinson added interlineations during the initial phases of composition, while additions inscribed sideways along the edges of the paper or traversing its center were added later, we cannot always be sure of this. Moreover, encoding does not reveal the absolute temporality of texts to which Dickinson returned sometimes not just moments, but months and even years after first working on them.

The very same problems and temptations confronting me in the encoding of text types inhered in the encoding of the material features of texts and documents—i.e., there seemed to be no limit to what might be marked, to what might be significant. To be sure, the original location of the manuscript (bound, unbound, among Dickinson's papers, outside Dickinson's private archive), the composition dates or range of dates of a text, the state (fair-copy, rough-copy, etc.) of a text, and the medium (ink, pencil) in which it was composed must be noted, but what of the orientation of the page and the direction of the writing (marginal writing, cross-writing, etc.)? ✝ Creating viable and defensible dates for Dickinson's late writings, especially her fragments, is challenging, and perhaps even impossible in cases where there is no corroborating contextual or paper evidence. The evidence of handwriting, though useful for determining the general period of Dickinson's career ("early," "middle," "late") to which a text belongs, is of less use for determining the exact year of composition—especially for Dickinson's late compositions. The difficulty of assigning composition dates on the basis of handwriting is particularly acute in the case of Dickinson's late rough-copy drafts, where handwriting evidence is often contradictory. Although I may be accused of excessive caution, I do not assign Dickinson's fragments to specific years, but only to the late period of her writing career, c. 1870–1886. I have assigned fragments to this date-range even in cases in which fragments reappear in other documents that can be assigned more precise composition dates because the fragment-traces were not necessarily composed at the same time as the texts in which they appear. The date-range for the fragments may of course be narrowed when paper evidence is present—that is, we may assume that a text inscribed on a piece of WESTON'S LINEN 1876 was not composed before 1876. The date-ranges to which I have assigned fragments (and related texts) are recorded in "Code Summaries" accompanying the documents; in the entry for "Date" in the "Physical Description" heading for each fragment I have recorded, in brackets, the dates assigned to the fragment by Thomas H. Johnson in Poems (1955) and/or Letters (1958), and by R. W. Franklin in Poems (1998). R. W. Franklin dated documents, as opposed to texts, and thus each document is, generally, assigned a single composition date. Thomas H. Johnson seems to have dated texts rather than documents, and, at times, he assigned different composition dates to discrete texts inscribed on a single document. Thomas Johnson did not have all of Dickinson's manuscripts at his disposal during his editing of her writings. A number of fragments which he might have included in the notes to the poems or letters to which they have links—had he had access to all of the documents at once—he placed instead among the "Prose Fragments" (see Letters [1958]), all of which Johnson imagined belonged to the last decade of Dickinson's life. In cases where Johnson cross-references a fragment placed in "Prose Fragments" with another, more precisely dated text, I have given both dates (["about 1873 or last decade"]) assigned by him. Similarly, the determinations of "state" made here are open to revision. The terms "rough copy," "intermediate copy," and "fair copy" are not ideal terms with which to describe the many documents of an essentially private nature found in Dickinson's private archive. In order to distinguish a fair copy sent out of Dickinson's archive from one housed within her archive, I have added the word "draft" to the latter category. The vast majority of the fragments appear to be rough-copy drafts. What about the various different positions—supralinear, sublinear, marginal, etc.—of Dickinson's additions, and of the different forms—single strike-outs, cross-hatchings, erasures—of her deletions? And what of the textual gaps created as the result of physical damages—scissoring, tearing, rubbing out, etc.? An outsider to the field of textual scholarship might glance at the long list of codes in the Library of Search Paths in Radical Scatters and conclude that it had been imagined by someone too long locked up with her materials. Who cares if the top edge of a document is torn? And who cares if a barely visible line is drawn along this tear? Still, the features may have meaning. In these particular cases, as I later discovered, the torn edge with the accompany pencil line indicated that the text had once been the final lines of another text, or a variant of those lines. Just so, many of the other physical features of the texts and documents, however insignificant they initially appear, may be clues to Dickinson's compositional practices and to the relations between and among her writings. At times, moreover, the manuscripts have iconic value, serving as a metaphorical as well as actual containers for thoughts: an envelope shaped like a bird carries a text about flight; a seal becomes a space for Dickinson to mediate on the power of secrecy; a torn edge corresponds to a textual verge; the two sides of a manuscript are inscribed with rhyming texts—or texts that cancel each other out. The medium and the message are sometimes one and the same.

The patient encoding of Dickinson's manuscripts and texts allows us, as John Bryant remarks of his editing of Melville, "to access more than before the otherwise unwitnessable workings of [her] writing and culture" (39). In the end, however, what encoding reveals most fully are the unruliness of the fragments and the folly of establishing a set of fixed principles with which to approach them. Like Dickinson herself, the editor/encoder must recognize the conflicting pressures and considerations attending each moment of the compositional process and concede the impossibility of offering a belated resolution of that conflict via the editorial process. So far, the encoding schema of Radical Scatters has received very little notice. Yet this schema, so ugly to look at, is the most essential aspect of the archive's critical apparatus, for it offers a deep, if also deeply embedded, record of the editorial process and makes manifest what is ordinarily concealed, i.e., its essentially contradictory, provisional, and subjective nature. In an uncanny doubling, the vision of the writer at grips with her traces is mirrored by the vision of an editor in extremis, sorting through scattered fragments in search of their order. The encoding schema thus reveals something further, and perhaps unexpected; that is, that writer and reader/editor always exist in what John Durham Peters has called a "shattered communication situation" (149). Across the wastes of time and space, there are no sure signs of contact between them, only an adventure in hermeneutics, "the art of interpretation where no return message can be received" (Peters 149).

The Question of the Path: Reading Recursively in the Archive

The continued survival of the Radical Scatters archive depends upon the fruitfulness of the research paths it opens and, more generally, on the realization of the potential of electronic resources to spur a re-imagination of scholarly and creative pathways. Indeed, most importantly, Radical Scatters offers a new site for what Paul Virilio, in his recent book Open Sky, calls "trajectivity," remarking: "It seems we are still incapable of seriously entertaining this question of the path, except in the realms of mechanics, ballistics or astronomy. Objectivity, subjectivity, certainly, but never trajectivity" (24). Since Radical Scatters does not, properly speaking, have an "end" (it does, of course, have a limit), the viewer does not direct him- or herself toward its final destination, but, instead, immediately takes up the question of the path. The power of the archive is, precisely, the power to induce a departure: "And I wonder," with Mireille Rosello, "if it may not be desirable at this point to experiment widely with disorientation rather than safety" (139).

Initially, however, several paratexts, including a comprehensive Site Map offering a visual overview of the levels of the archive, indices of the documents in the archive arranged by type, libraries of codes and search paths, a library of Dickinson's "hands," files of bibliographical and critical glosses on the fragments and related texts, and an appendix of the earliest printed sources of Dickinson's fragments, help to orient the reader and facilitate a large number of critical and analytic operations. ✝ While it is not possible to describe in detail the numerous paratexts, a note on the Library of Search Paths and the Hand Library seems in order. The Library of Search Paths offers an extensive list of possible search paths. From this library readers may search across the archive for documents falling within certain generic categories (fragment, poem, letter, etc.); for documents falling within certain composition dates (early, middle, late); for documents belonging to particular file types (bound documents, unbound documents, mailed documents); for documents composed on various paper types; for documents composed in different media (pencil, ink); for documents composed in different hands (rough, intermediate, fair); for documents evidencing specific material characteristics (torn edges, scissored edges, etc.); for documents evidencing specific scribal practices (additions, interlineations, cancellations, cross-writing, etc.); for documents marked by editors; and for documents housed in specific collections. Simple, boolean, and proximity searches of all Dickinson's texts contained in the archive, as well as the critical commentaries accompanying them, may be initiated from the Library of Search Paths. The Hand Library offers examples of Dickinson's different handwriting styles and allows readers to trace a particular "hand" across the archive. All of the primary materials in the archive—fragments and related texts—are organized for full electronic search and analysis, and all are embedded in a complex hypertextual environment that makes possible the study of macrogenetic phenomena (i.e., phenomena occurring across the documents in the archive) and the analysis of microgenetic details (i.e., the salient features of individual documents). While the non-hierarchical or decentered structure of the archive reflects the fragments' irreducible singularity and insusceptibility to collection in a "book," the archive's system of nonlinear links reveals, on the other hand, their openness to and participation in multiple textual constellations and/or contingent orders. At times the close study of elements and attributes of a given document will delimit the trajectory of an exploration. At other times, the exploration of document constellations leads readers to new discoveries. And, finally, readers may act as "shifters," cutting their way across the various levels of the archive by following a single code or combination of codes.

The number of codes, types, searchable fields, and links is finite and editorially determined; yet the number of paths that can be traced through the materials, is almost limitless—or, rather, limited only by the reader's willingness to track individual codes, attributes, and elements and to collate search results, or by his or her imagination of combinatory possibilities. In general, then, the best readers of Dickinson's fragments will not read linearly but recursively, finding, often by losing, their different ways through the archive. The paths traced by the reader through the electronic archive are the "traveler's tales" that, in Open Sky, Virilio fears will be lost, along with "the possibility of some kind of interpretation," on the information superhighway (25). To be sure, there are risks. As Mireille Rosello writes, since the "screener's navigation . . . [is] both read and written at the same time. . .meaning. . .[becomes] fragile, easily destroyed, [almost] impossible to record" (148). ✝ I have added the bracketed word "almost" to Rosello's passage since a number of experimental interfaces such as "Information Visualizer" (XeroxPARC) and "Abulafia" seem to promise the possibility of virtual memory; for further information, see Gunnar Liestøl's essay "Wittgenstein, Genette, and the Reader's Narrative in Hypertext," in Hyper/Text/Theory, 87–120. Yet however fragile, illegible, or quickly erased these virtual itineraries (the inscription of which begins the moment the reader—the screener—enters the archive and ends only arbitrarily when he or she exits) may be, they are also new signifying (critical, creative) narratives that we cannot ignore and that require a new theory of reading.

A Traveler's Tale" Following "A Woe / of Ecstasy"

Let us, by way of ending, follow a single fragment for a few moments further. ✝ The reading of A 112 was first offered in my essay "'Most Arrows': Autonomy and Intertextuality in Emily Dickinson's Late Fragments," TEXT 10 (1997): 41–72.

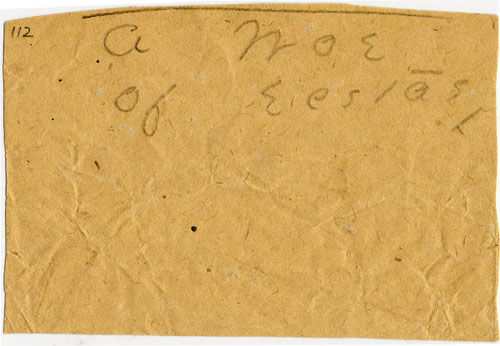

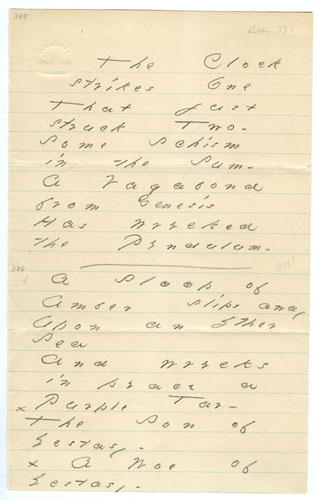

Among Dickinson's textual remains, on a scrap of brown wrapping paper, we find this excruciating offering: "A Woe / of Ecstasy" (A 112).

Focus 6: A 112. Last decade. Lines penciled on a scrap of brown wrapping paper now measuring approximately 60 x 96 mm.

In this case, the fragment exists in two textual spaces at once: as an autonomous lyric throe and as a variant or rhyming trace of the final line of "A Sloop of Amber slips away," composed around 1884. ✝ In fact, this brief, extrageneric fragment appears as a trace in two other documents, both composed around 1883 (RWF) or 1884 (THJ): first, in the text cited here, a fair-copy poem-draft, with alternatives, beginning, "A Sloop of | Amber slips away" (A 386), where it appears as the final (variant) lines of the draft; and second, as a "rhyming" trace (text altered) in a fair-copy of the same poem incorporated into a fair-copy pencil letter-draft [about 1883 (RWF); 1884 (THJ)] possibly intended for Professor Tuckerman but never apparently mailed (see A 836).

Focus 7: A 386. About 1883 (RWF), about 1884 (THJ). A fair copy pencil draft of a poem on wove, off-white, blue-ruled stationery embossed CONGRESS above a capitol and measuring approximately 202 x 126 mm. It has been folded horizontally into thirds.

To be sure, something is negotiated between the fragment and the poem held spellbound for an instant—not least of all the poem's boundaries. But unlike the lists of variants that stream after so many of Dickinson's poems of the 1860s, this fragment is neither materially nor syntactically subordinated to the poem proper. On the contrary, "A Woe / of Ecstasy" rhymes with its variant—"The Son of Ecstasy"—and re-enters the drive of writing—a "presence after presentness" (Steiner 147). Only the barest signs of a struggle remain: in the poem, three dashes rend the text at the points where the fragment migrates into it and then disengages from it again, while along the top edge of the fragment, a light horizontal line, like the lines Dickinson sometimes drew to separate the body of a poem from its variants, and, later, to divide tiny increments of thought, is a graphic sign that these lines were once the last lines of a poem since torn away. Now the end, the "variant," has become a new beginning. Outside the labor of the poem's argument, alone again, the fragment seeks the exact conditions for poetry while extending, exponentially, the original impetus of fragment, poem, and oeuvre toward openness. A trope, or turn, "A Woe / of Ecstasy" does not so much orient the poem in which it appears as a citation as illuminate the inner contradictions—the paradoxes and antinomies—out of which all of Dickinson's writings are engendered.

Towards a "Chaology of Knowledge"

I discovered the title for Radical Scatters by accident in a book by G.V.T. Matthews on the migratory patterns of birds. ✝ G. V. T. Matthews, Bird Navigation (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1968), 49. In order to determine whether or not certain birds possess homing instincts, a person known as a "liberator" throws several birds into the air one at a time, each released in a different direction. The birds are then watched out of sight, and the points at which they disappear from view are recoded. When a statistically significant number of vanishing points have been noted, a chart called a "scatter diagram" is drawn up for study. At times, for reasons not entirely understood, some birds on the outward course drift widely across the migration axis. These drifts, called "radical scatters," both solicit and resist interpretation. Dickinson's late fragments are textual counterparts of the scattered migrants. As I noted at the opening of this essay, they fly beyond the ending of the codex book to the lyrics many ends. No archivist-editor-scholar can hope to bring about their harmonious synthesis. Rather, they requite an alternative method of presentation, a new paradigm based, perhaps, on what Ira Livingston calls "a chaology of knowledge" (vii). Instead of classifying the fragments according to conventional bibliographical and generic codes, we need to find ways of not naming them as they flash by; instead of binding them into chronological order in a codex book, we need to find new ways of launching them into circulation again and again in the hopes of illuminating the tensions and freedoms at the heart of Dickinson's late work.